Bertolotti Syndrome and Scoliosis

Who is Bertolotti and what the heck is the syndrome named after him? This is a question I found myself asking earlier this week, after spotting a large bony abnormality on a patient’s x-ray. As I was scanning her lumbar spine in the image, my eyes came to rest on the 5th lumbar vertebra, or more simply, “L5”. Instead of having dainty protrusions on each side of the vertebra, called transverse processes, she had massive bowtie-looking bones extending from both the left and right sides of her L5. Whaaaaaaat?

X-Ray of Bertolotti Syndrome in the left L5-S1

Enhanced imaging of Bertolotti Syndrome in the left L5-S1

Even weirder, the big bone protruding off the right side of her vertebra looked continuous, or fused, with the sacrum bone below it! L5 and S1 (the top of the sacrum) are typically two separate bony entities, joined together only by ligaments on each side, forming facet joints.

I always knew it was possible for the lumbar spine to be congenitally fused with the sacrum, but I had never seen it in clinical practice. I reached out to Dr. Adam Wegner, an orthopedic spine surgeon in Arlington, VA, to inquire about his experience with Bertolotti Syndrome. Turns out he is a wealth of information on the subject – he feels it’s an obscure and often missed spine diagnosis. (According to NIH, Bertolotti Syndrome affects 4-8% of the general population.¹)

He has diagnosed and treated many, often in patients who have been looking for an answer for their back pain for many years.

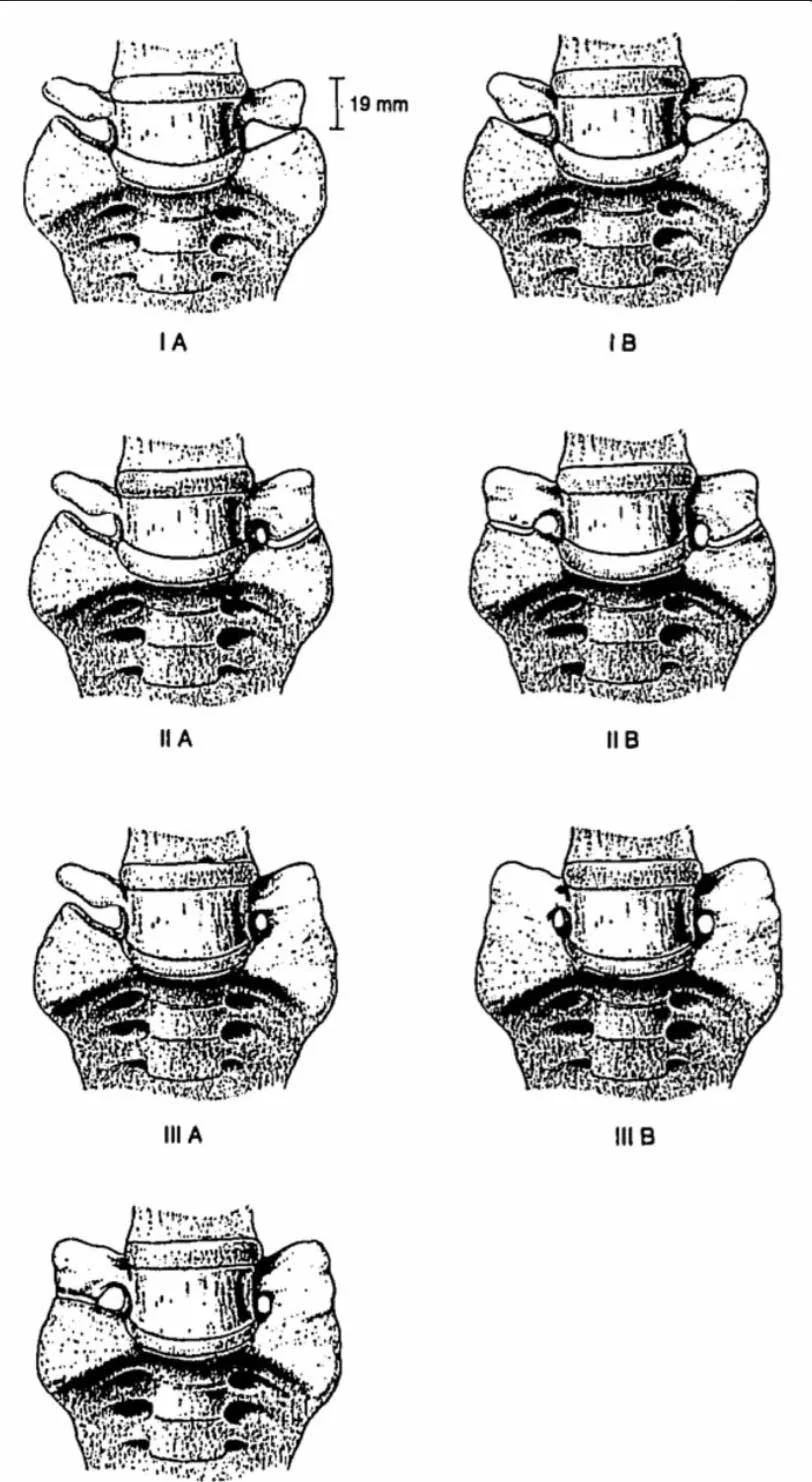

Jenkins Classification System

Mario Bertolotti was an Italian physician who first described this condition in 1917. Dr. Arthur Jenkins III, a neurosurgeon at Mount Sinai, more recently developed a classification system for Bertolotti Syndrome. This classification system is based on whether there is unilateral or bilateral lumbosacral transitional vertebra (LSTV), or “extra bone”, and if the LSTV is pseudo-articulating with the sacrum, or fully fused to the sacrum.

For years, the medical field denied that this congenital anomaly would cause any pain to its recipients. And to be fair, most individuals who are born with Bertolotti’s won’t experience any symptoms until the 2nd or 3rd decade of life, even though it’s been there all along. Luckily, times change and the modern-day medical community is admitting that this can be a problematic issue. The abnormal mechanical stress caused by Bertolotti’s can result in many different generators of pain: facet joint arthropathy, strain of the iliopsoas and quadratus lumborum muscles, nerve compression, and disc herniation in L4/5 or L5/S1 segments. Patients will often report very localized pain in the lumbosacral area – think the very lowest part of the spine, almost the buttock area. At times this condition can inflame the L5 nerve root and cause sciatica-like symptoms down the back of the leg.

So how do we properly diagnose Bertolotti’s? An X-ray of the lumbar spine and pelvis is the quickest, easiest, and cheapest way to begin. This reveals the bony anatomy of L5, just like in my patient’s x-ray. The limitation of X-ray is that it can be difficult to see if that extra bony protrusion is simply forming a false joint (i.e. pseudo-articulation) with the sacrum or if it is continuous (i.e. fused) with the sacrum. If more information is needed, the patient will be sent to have either a CT Scan or MRI. The reason this matters: medical treatments will differ depending on if the bones are fused or not.

Once diagnosed, the first line of treatment is 6 weeks of physical therapy plus oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) – Naproxin, Mobic, and Celebrex to name a few. If symptoms persist, orthopedists will refer the patient to a pain-management physician to do 2 rounds of steroid injections into the site. If the first or first and second injection provide pain relief, and the pain doesn’t come back, excellent, the patient is sent on their way. If the injections provide only temporary pain relief, surgery becomes an option. If the bony protrusion is small enough and not forming a pseudo-articulation to the sacrum, the surgeon will simply remove it. If it has formed a false joint with the sacrum, the surgeon will heavily consider fully fusing it to the sacrum rather than taking it out. They don’t like to do the latter in young patients, but they feel as though a small fusion is better than chronic pain, and most patients are agreeable.

Ok, let’s get to the most important part of this post: what does Bertolotti Syndrome have to do with scoliosis?! Although good old Wikipedia tells us scoliosis is frequently found to be associated with Bertolotti Syndrome, we need to look to more medically reputable sources to confirm this. In a study done by NIH of 20 patients with Bertolotti Syndrome, all 20 patients had scoliosis(!!)². There’s no great description in the medical archives as to why Bertolotti may cause scoliosis, but the physical therapist in me looks to the basic principles of physics to explain this. If just one side (i.e. unilateral) of L5 is tethered to the sacrum via an LSTV, and the other side is free to move, it makes sense that the side that is tethered/fused/not moving would cause asymmetrical loading of the pelvis – in simple terms, one would begin to sit or stand to that side of the tethering, thus beginning the vicious cycle of scoliosis that we discussed in our last blog.

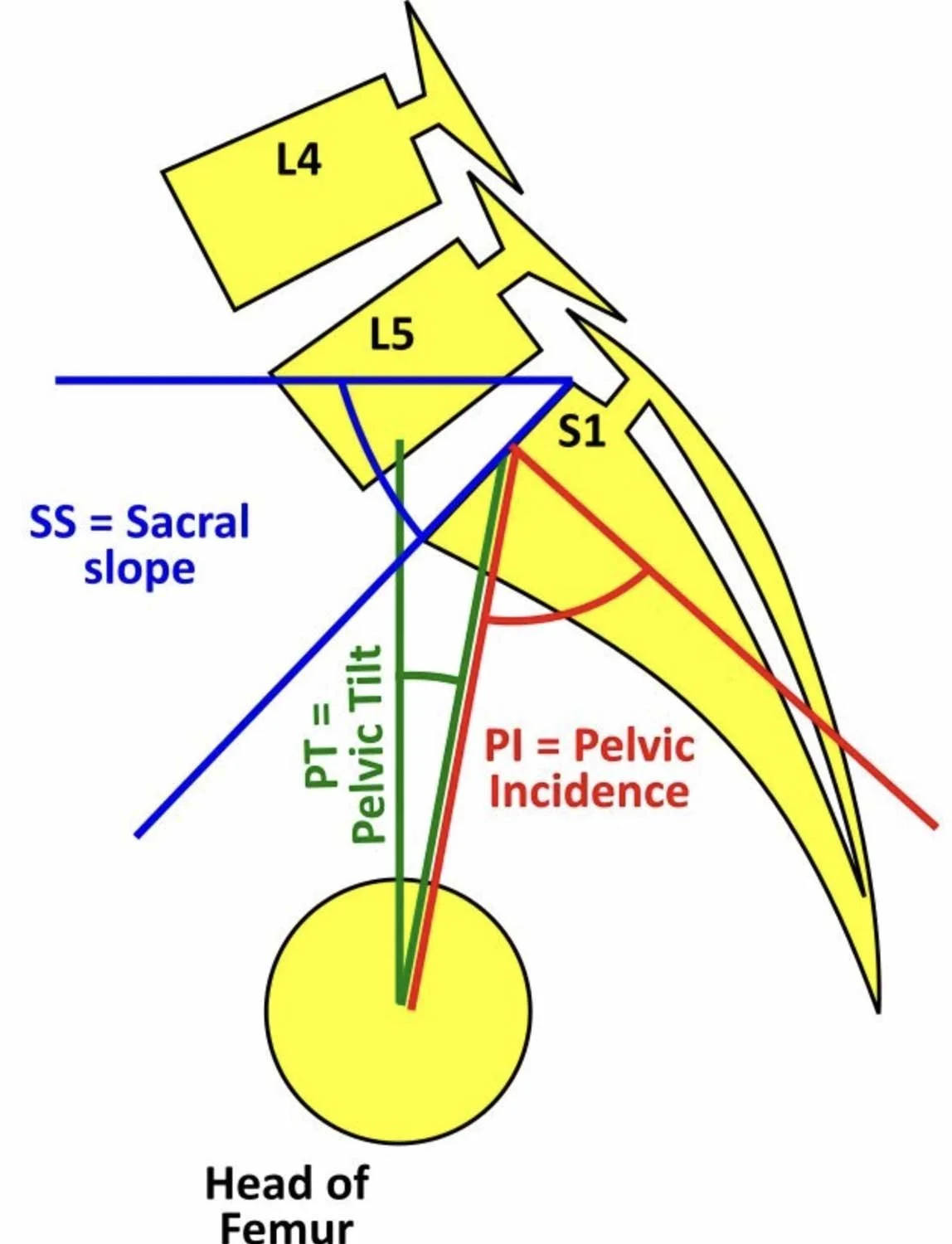

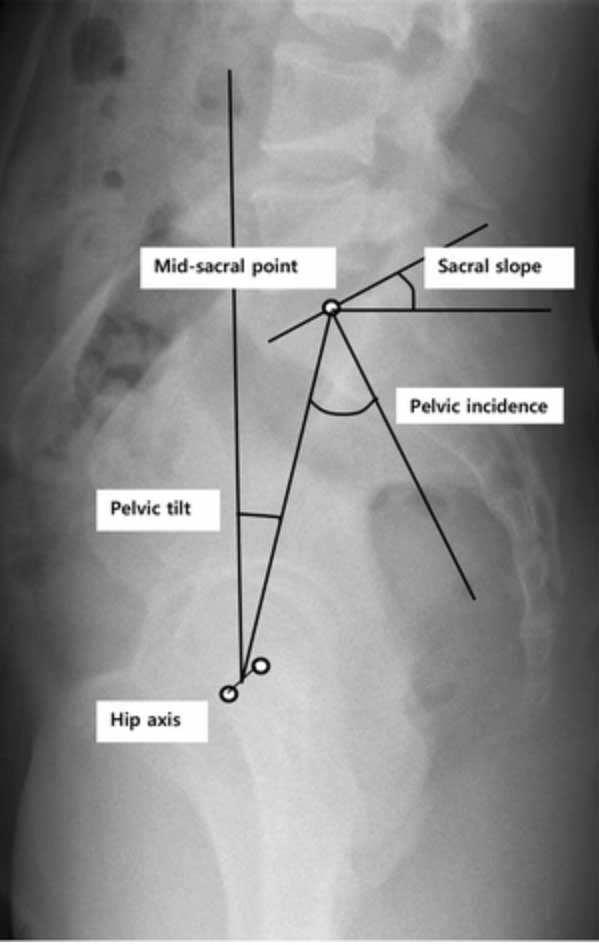

Dr. Adam Wegner thinks the association has more to do with a measurement called Pelvic Incidence (PI). PI is the angle between the line perpendicular to the sacral endplate at its midpoint and a line connecting this point to the axis of the femoral head.

Pelvis Incidence

Pelvis Incidence X-Ray

Patients with scoliosis often have a low Pelvic Incidence, and often times a low PI can be the result of transitional anatomy, such as LSTV.

Certainly, in our clinical practice at SchrothDC, we see scoliosis and Bertolotti Syndrome going hand-in-hand. Here is an example of a unilaterally-fused LSTV pairing with scoliosis on X-ray:

Given that a referral to physical therapy is the first line of defense for Bertolotti Syndrome, we feel confident that the Schroth Method can be a key piece of management for this condition.

References: